Film Room: The Sweep and the Sucker

By DustyEvely

“Every football team eventually arrives at a lead play. It becomes the team’s bread-and-butter play; the top priority play. It is the play that the team knows it must make go, and the one opponents know they must stop…My number 1 play has been the Power Sweep…there’s nothing spectacular about it; it’s just a yard gainer.”

So begins Vince Lombardi’s coaching video on his famed Lombardi Sweep. While Lombardi did not create the Power Sweep, it’s hard to think of a play more tightly connected to a coach. Lombardi saw the play not just as a play, but as a guiding ethos. “It requires all 11 men to play as one to make it succeed, and that’s what ‘team’ means.”

Today, we’re going to dig into the famed Lombardi Sweep, talk about what made it work and look at a few of the major counters that Lombardi would break out once teams started keying in on it (including one counter that came in one of the biggest moments in one of the biggest games in Packers history). You ready? I’m ready. Let’s do it.

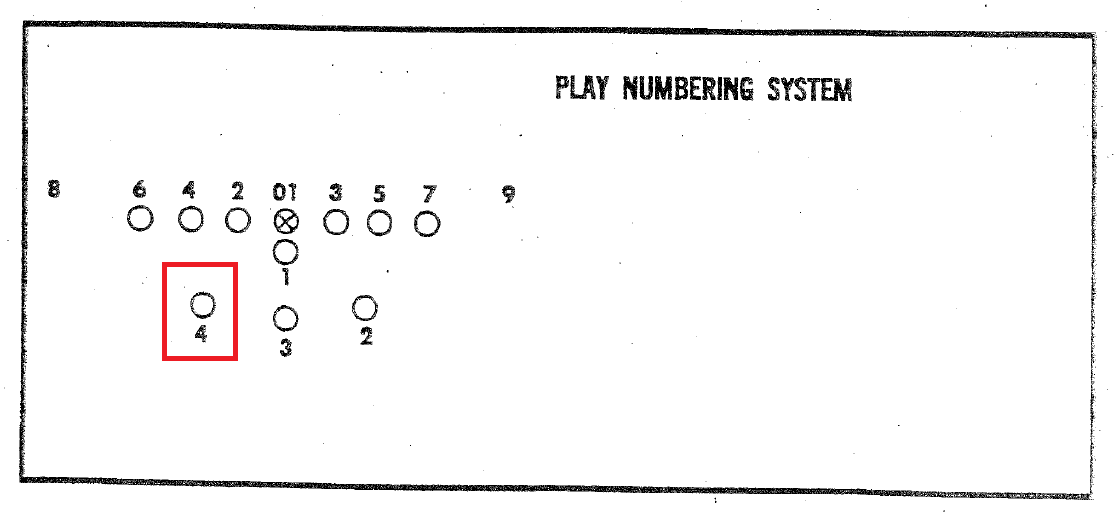

The 1966 Packers playbook has the Power Sweep prominently featured – as you may have guessed – but it’s not labeled as the Power Sweep, because things are not that simple. The actual playcall was 49 Strongside, because it was telling the “4” back…

…to run to the 9 hole.

…which would be on the strongside of the formation.

Easy enough, right? We’re going to look at a handful of plays, but the only film for the plays themselves are from broadcast, which consist of pretty tightly cropped shots. To get a better feel for all the moving pieces, I thought it would be helpful to look at the playbook diagram itself.

The overall idea is pretty simple from a blocking perspective: the pulling right guard blocks to the boundary, while everyone else is looking to seal off the inside. The pulling left guard essentially works as the lead blocker for the running back. While the Packers are aiming for the 9 hole, the left guard is looking to run through the first bit of daylight he finds, and the running back will follow him.

When Cliff Christl interviewed Bill Austin – Green Bay’s offensive line coach from 1959-1964 – about the technique of the pull guards, he unleashed a tremendous quote: “There was no particular key to it. If you saw a guy standing there, you knocked him down.”

Of course, there’s a lot more to it than that, but that’s the overall idea.

If you want to boil it down to its most basic component, you don’t need to look any further than Lombardi himself.

Now that we all have a pretty good grip on the mechanics of 49 Strongside, let’s look at a few examples.

The Bears are crowding the line, looking like they’re bringing pressure. That changes the blocking a bit, specifically when it comes to the block from Jim Taylor [31]. His usual assignment is to clean-up the DE who had been chipped by the RT (in this play, that RT is Forrest Gregg [75]). But with the extra man on the end, Taylor cuts that man, giving Jerry Kramer [64] the release he needs on the pull.

Kramer clears the edge and doesn’t find anyone in the immediate vicinity. I love watching him truck down the field and desperately looking for someone to clobber.

Now, this play is a little different than the diagram, in that Fuzzy Thurston [63] cut blocks from his position at LG while Norm Masters [78] pulls from the LT position.

This next play has a tighter view, but is more in line of what we think of with the traditional sweep. A couple cut blocks, a slam/release from the RT as he climbs to the linebacker, and then the beauty and majesty of Thurston and Kramer pulling and creating an alley for the running back.

Lombardi had a lot of very specific coaching techniques for The Sweep, but there was one key point he harped on: when blocking on the sweep side, the one thing you cannot do as a blocker is to allow inside penetration on the play. If the defender gets penetration wide, that’s fine because the back can cut inside. But penetration to the inside on even a single block could blow up the play.

On this play, you can see Kramer slightly altering his path on the edge to make sure he blocks his man to the outside and washes him out of the play.

On this play you can also see that Jim Taylor was a monster.

Here’s a few more examples of The Sweep, just because.

I’ll end this section with one of my favorite versions of the traditional Sweep, run from a slightly less-than-traditional look. The end look is the same, but the initial releases from the guards are different. They look as if they’re releasing to the left, then spin back to the right.

It’s a beautiful bit of synchronized ballet from Thurston and Kramer, and it’s certainly a product of the single-wing game that Lombardi came up in. The main difference between this play and 49 Strongside is the release of Jim Taylor. Instead of blocking the end, he carries out the fake to the left side of the formation, getting the defense to lean in that direction. In this instance, Lombardi sacrificed a blocker in the service of misdirection, and it paid off.

Of all the plays I looked at for this article, this is my favorite.

Counters

That brings us to our series of Counter plays. While the Sweep was Lombardi’s lead play, he was never under any illusions that it would work no matter what the defense did. “I never meant that team could not stop the sweep, but to do so they had to make unusual adjustments. In making those adjustments it left them vulnerable to plays that looked like the sweep but took advantages of the defense and its changes.”

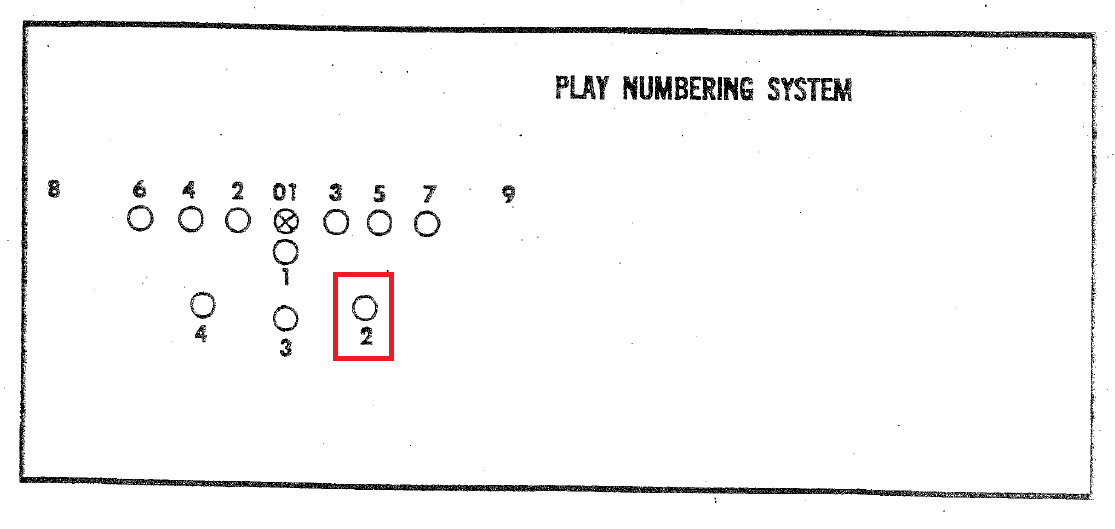

28 Weakside

The first counter to bring up would be Sweep to the left, or, to use the playbook terminology, 28 Weakside. Like 49 Strongside, this call told the 2 back…

…to run to the 8 hole…

…which would be to the weakside of the formation.

It wasn’t called often – Bill Austin estimates that it was only called 10% of the sweep calls – but it was used.

As the naming would tell you, it was run to the weakside of the formation, which means there is one less blocker. The wide receiver - or “flanker” - is set wide to the right. It is his job to seal the safety. Running to the weakside means they didn’t have that blocker. That’s the main reason it was so seldomly used. Lombardi only called it when the defense started rotating their safeties over to the strongside. In Lombardi’s words, they made an “unusual adjustment,” in which case the Packers would run this counter. There’s not a huge need to block the safety if he’s rotating to the opposite side.

Here are a couple other examples of 28 Weakside.

49 Sweep Pass

This counter was designed to make the defense pay for aggressively pulling their safeties up to crash The Sweep.

The blocking motion is the same as The Sweep. From the slam/release from the right tackle to the clean-up by the FB to the pulling guards. The goal is to trigger the secondary into firing down, then hit them downfield with a pass. The first read is to the wide receiver (“flanker”), who releases as if he’s blocking the safety, then releasing on the corner. If that’s not open, the next look is to the flat

If that isn’t open, it’s likely because the defense is sitting back and anticipating the pass. In that case, the running back simply shouts “run,” and the blockers in front continue blocking for the sweep.

By simplifying the reads for the RB and playing off a key concept, it’s a really nice way to look to hit a big play down the field. If the big play isn’t there, it likely means there’s a good opportunity to pick up some nice yardage on the ground.

45 Trap (“Long Trap”)

Another key counter Lombardi used was 45 Trap, or “Long Trap.” Much like 28 Weakside, Long Trap was designed to exploit a defense that had made an “unusual adjustment.” In this case, the unusual adjustment would be the defensive end aggressively trying to get outside the right tackle and take away the outside sweep lane.

Instead of blocking out, the line blocks down, looking to isolate the defensive end. The fullback drives him out, the pulling left guard cuts inside and the halfback follows the pulling guard.

Really nice variation to make the defense pay for trying to take away the outside.

Give 54 (“Sucker”)

We come now to my favorite variation. In fact, it was this variation that led me to this entire article (for better or worse). Though it is called Give 54, everyone just calls it “Sucker” and it is designed for one very specific purpose: to punish an overly aggressive interior defensive line.

With the Packers having a lot of success with The Sweep, teams wanted to stop it. One of the ways to stop it would be to shoot the gaps in the line created by the pulling guards. Pulling the guards leave a natural – if short-lived – void in the line. The Packers were good at covering those up with the other blocking assignments, but it was an area where The Sweep could be beaten. Take this play from the final drive of the Ice Bowl in 1967:

That’s Willie Townes [71] breaking through the line and making a tackle behind the line of scrimmage for a loss of 7. Sucker was specifically designed to counter this.

Get the defensive tackle looking to shoot the gap to make a play in the backfield, then give the ball to the fullback who attacks that hole created by the shooting DT.

For a little added oomph, you could also have the running back crack down on the defensive tackle, as we see in the above clip.

Now…

All of this we just covered, leads me to this next play. This is the play that kicked off the entire idea of looking at The Sweep. In Keith Dunnavant's America's Quarterback, Starr called it “the greatest call I’ve ever made...that [play], in my opinion, was the key play in the game.”

I showed the tackle for loss by Townes on the final drive. The Packers were trailing 17-14. A few plays after the Townes tackle, the Packers were looking at 1st & 10 at the 11 yard line with 1:11 left in the NFC Championship Game. Then Starr dials up Give 54.

The man they’re keying is Hall of Famer Bob Lilley [74]. The 1967 season saw Lilley earning First Team All-Pro for the 4th consecutive season (he would also pick up First Team All-Pro Honors in 1968 and 1969, for a run of 6 consecutive years receiving that honor). They were banking on Lilley looking to blow up The Sweep, leaving a gap in the middle of the field wide open.

That’s exactly what happened. Lilley is looking to shoot through the line and blow up the sweep. By the time he sees what has happened, Chuck Mercein [30] has shot through the line. Mercein rumbles down to the 2 yard line.

And then, of course, a few plays later…

Years of setting up The Sweep. Running it until every member of the offense could carry out their assignments in their sleep. Becoming the very foundation on which those Packers teams were built. Their lasting identity to this day. To go back to Lombardi, “It is the play that the team knows it must make go, and the one opponents know they must stop.”

Then, in one of the biggest moments in a game that would become an instant classic - and later revered as one of the most memorable games in NFL history - they run a beautiful counter for a big gain. Talk about setting up your tendencies and running counter to them at the perfect time, man.

I hope you all liked this deep-dive into this concept. Throughout the offseason, I’ll be digging into some other iconic plays from the Packers history. They won’t all be this long, but, since this was The Sweep, I felt it deserved a little more time. I already have some plays lined up, but if you all have anything in mind you’d like to see covered, let me know.

Oh, and a little nugget on The Sneak. The Packers didn’t have a QB sneak in their playbook, so the call was 31 wedge, which called for Mercein – the “3” back – to run to the “1” hole. Due to the state of the field and the fact that the running backs were having a hard time getting their footing on the previous 2 plays, Starr kept it himself. According to Jerry Kramer (in Instant Replay) and Forrest Gregg (in Winning in the Trenches), Starr came to the huddle and said, "31 Wedge and I'll carry the ball." Apparently Chuck Mercein was not privy to that information. In Mark Beech's The People's Team, Mercein wrote, "What I didn't know - since Bart didn't bother to tell us - was that he was going to keep the ball himself in order to avoid an possible problem with the handoff." So maybe Mercein didn't get the memo in the huddle.

When Starr told Lombardi he thought he had a better chance of getting in than the running backs, the response was perfectly simple and perfectly Lombardi: "Then run it and let's get the hell out of here."

Albums listened to: The Kinks – Something Else; Jimmy Smith – The Sermon; Bob Dylan – The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan; The Jimi Hendrix Experience – Are You Experienced; John Coltrane – A Love Supreme; The Beatles – Revolver; Thelonius Monk – Monk’s Dream; Love – Forever Changes; Sam Cooke – Night Beat; Nina Simone – Pastel Blues; Francoise Hardy – Tous les Garcons et les Filles; The Sonics – Here Are the Sonics; Dave Brubeck – Time Out; Albert King – Born Under a Bad Sign; The Velvet Underground – The Velvet Underground & Nico; Miles Davis – Sketches of Spain; Ray Charles – Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music; The Beach Boys – Pet Sounds; Cream – Disraeli Gears; Ike & Tina – The Soul of Ike & Tina Turner; Bill Evans – Sunday at the Village Vanguard

PLEASE SUBSCRIBE TO OUR CHEESEHEAD NATION WEEKLY NEWSLETTER HERE.

__________________________

Dusty Evely is a film analyst for Cheesehead TV. He can be heard talking about the Packers on Pack-A-Day Podcast. He can be found on Twitter at @DustyEvely or email at [email protected].

__________________________

Comments (6)

Since'61

March 17, 2021 at 03:52 pm

Kramer and Thurston, "Poetry in Motion." The thing about watching those old Packer clips is the excellence of the OL. If you notice they all come off the ball together at the same time. You don't see any of the OLs even a fraction of a second late off the ball. Second their footwork is excellent.

The next key factor is the play calling of Bart Starr reading the defensive adjustments and calling the correct version of the sweep or the correct version of the counter to exploit the defensive adjustments. He was one of the best play callers there has ever been. Again as Starr makes the appropriate play call the OL adjusts perfectly and makes their blocks.

I love watching Paul Hornung run. People question his HOF selection but when you watch him makes his cuts and break into the open field you can see just one of the many reasons he was chosen for the HOF.

Finally Dusty, your selection of plays showcased 5 different Packers RBs; Hornung, Taylor, Tom Moore, Elijah Pitts and Chuck Mercein. Each back is able to run effectively behind that great Packer OL. Proving once again that the offense goes as far as their OL takes them. Only one play has Donny Anderson, another good RB, taking a loss on an effective play by Willie Townsend. However, as you correctly pointed out that play helped to set up the counter which was so effective with Chuck Mercein later in the drive. If Hornung or Taylor was still there in '67 either one would likely have scored on that play. But then we would have missed out on the histrionics of Starr's QB sneak which just added more mystique to the Packers and the Lombardi legends.

I doubt we will ever see that crisp, sharp OL play ever again. The current CBAs just don't allow enough practice time for the players to get their blocks as perfect as Lombardi's OL. Those were the golden days of the Packers and the NFL. Thanks, Since '61

slant_route

March 17, 2021 at 03:50 pm

Congratulations on a very nice piece that I enjoyed quite a bit. Despite how different the game is one thing that stands out is that Green Bay in 2020-21 still is trying to make one thing look like another and then take advantage of it the defense's reaction. Love it.

wildbill

March 17, 2021 at 03:53 pm

Wow, what an excellent job! Thanks so much. Got to watch the Lombardi Packers but being young I didn’t understand all the ins/outs of the game.

malta1099

March 17, 2021 at 05:55 pm

That was amazing. Great job and so entertaining/educational!

It seems almost as if Lombardi was running the 'illusion of simplicity' while actually being quite complex in all its variations.

Keep 'em coming.

Swisch

March 17, 2021 at 06:47 pm

Born in 1962 at Columbia Hospital in Milwaukee, and age 5 at the time of the Ice Bowl, I was alive for many of the Lombardi years but oblivious to them -- yet those teams somehow captured my imagination when I was still in grade school in the early 1970s. I've reveled in them ever since.

In the 1980s, the sportswriter Dick Schapp looked back twenty years to the Lombardi Era and said those teams were the best in the history of all professional sports. Not necessarily the most talented, nor the most successful, but the best at getting the most out of individual ability for the greatest group performance.

It's the spirit of teamwork the current Packers need to capture through self-sacrifice to put them over the top in winning a Super Bowl or two.

***

We see some evidence above (in the treasure trove of Dusty's article, and the fine comment by Since'61) of the reasons the Lombardi Packers achieved legendary status.

In the Ice Bowl, the Packers offense had been stopped cold by Cowboys over the second half -- for a net of negative yardage -- when its last gasp came at their own 32 yard line, down by a field goal, with less than five minutes left.

The field was so frigidly hard that Boyd Dowler was literally knocked out of the game early in that final drive after he caught a pass across the middle and had his head hit against the ground.

Yet Bart Starr at last found a way to methodically move the offense down the field in the arctic air, utilizing not Taylor and Hornung, not Pitts and Grabowski, but Donny Anderson and Chuck Mercein on handoffs and short passes.

The unheralded Mercein, added to the roster at midseason from semi-pro football, gained half of the yards on the drive, including the counter play against Bob Lilly highlighted above.

The cleverness of that call by Starr, and the command he showed overall in the most adverse of conditions, shows how much more there is to being a quarterback than passes downfield.

Although Starr became an excellent passer in the NFL -- most notably in the previous season of 1966 when he was named league MVP -- what sets him apart as the best quarterback of all time was his mastery of the hundreds of little intricacies the go into the craftsmanship of this prime position.

This includes the subtleties of leadership that allow a man to take charge of his company without exalting himself. Along with his dedication to the physical details of the game was Starr's attention to the people around him. His absence of ego gave him a towering presence.

Starr has never been equaled in leading a team to three straight NFL titles, and to five championships in seven seasons. In ten playoff games over his career the Packers won nine -- and his statistics for those games are stellar.

In the clutch, it's not so much about schemes and systems as it is about people pulling together in the most trying of situations. In this the Packers of the Lombardi Era excelled without any rival in sports history.

It's there as our heritage not only for the current Packers to commit to memory, but to emulate for glory.

***

Enjoy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J1YgxWWBt3o

PeteK

March 17, 2021 at 07:30 pm

Reverse sweep , never saw that, excellent!! Thanks for the nostalgia.